Ken MacTaggart, Scotland

He was the command module pilot on the first long-duration Apollo mission, and conducted extensive scientific experiments during his three days of solo orbiting of the Moon.

Alfred Worden, who died aged 88 near Houston, Texas on 18 March 2020, was a member of the select band of only 24 humans to travel to the Moon during the Apollo program of the 1960s and 70s.

Always known as Al, he was one of the liveliest and most approachable of America’s early astronauts, and a regular visitor to Europe.

Worden’s astronaut career started with his selection as a member of NASA’s fifth intake in 1966. He and eight others of his group would go on to make lunar flights. His first assignment was on the Apollo 9 support crew for its 1969 Earth orbit flight, then as back-up Command Module Pilot for the second Moon landing mission, Apollo 12. After that mission returned safely, Worden was selected in late 1969 to fly on the much more ambitious Apollo 15.

After two of his classmates, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise, survived the near-disaster of Apollo 13’s abortive attempt at the third Moon landing, NASA slowed the pace of the Apollo program. Worden’s 12-day flight was eventually launched on 26 July 1971, on the heaviest Saturn V rocket to date. His commander Dave Scott and lunar module pilot Jim Irwin planned to spend a record three days on the lunar surface and conduct wide-ranging geologic exploration, using the first electric two-seater rover vehicle.

While his colleagues landed at the Hadley-Apennine site in the Moon’s northern hemisphere, on a cratered lava plain below some of the highest lunar mountains, Worden orbited the Moon solo in his spacecraft Endeavour.

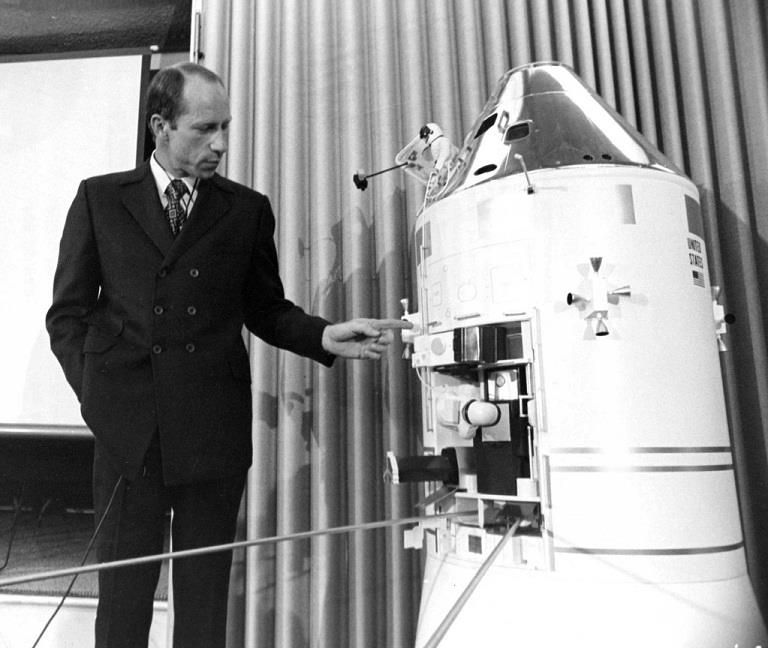

Worden had a key scientific role complementing the more glamourous surface activities, surveying Falcon’s landing site from above, and mapping a quarter of the lunar globe. He ran an extensive programme of scientific observations with mapping and panoramic cameras, gamma-ray and X-ray spectrometers and a laser altimeter. He put his geologic training to use in landscape observations and he pinpointed the landing site for the final mission, Apollo 17.

Although his orbital role in Endeavour may have seemed less glamorous than landing, it required much more technical flying skill. His three days of solo travel in lunar orbit, half of it spent out of contact with mission control on the Moon’s far side, made a deep impression on Worden. The experience stimulated his unique book of poetry entitled Hello Earth, published in 1974.

When the lander Falcon returned from the surface to lunar orbit, Worden achieved a smooth docking to enable his crewmates and their priceless haul of moon rocks to re-join him in the Command Module. The crew continued experiments in lunar orbit for a further two days and released a small scientific sub-satellite to study the lunar environment. The little satellite continued its independent flight for 18 months, radioing its measurements back to Earth.

The day after leaving the Moon for home, Worden made the first-ever spacewalk in deep space, 300,000 km from Earth. He floated out of the hatch attached to a cord held by Irwin and crawled down the sun-blistered hull of the Service Module to retrieve the data and film cannisters from his scientific instruments.

All previous spacewalks had been in near-Earth orbit, where the planet fills half the view. Now, Worden was floating in the void between Earth and Moon, seeing both as distant globes. Glancing back towards the hatch, Worden was awestruck at what he would later call one of the most amazing sights of his life: “Jim, you look absolutely fantastic against that Moon back there. That is really a most unbelievable, remarkable thing.”

Returning to Earth on 7 August, the Command Module made its flaming re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere. One of the three parachutes collapsed after deploying, due to damage as the spacecraft vented corrosive fuel, but fortunately only two ‘chutes were required for a safe splashdown.

Apollo 15 was Worden’s only spaceflight. He and his unlucky crewmates were made something of a scapegoat by NASA in 1972 over souvenir postal covers they carried in their personal kit, a common private practice that management had turned a blind eye to on previous spaceflights. Following a law suit in 1983, the government returned to the crew over 350 stamped envelopes seized by NASA. The judgement concluded that the space agency had either authorised their carriage on the Apollo 15 spacecraft or had known that they were taken aboard.

Already in training as the back-up crew for Apollo 17, the final Apollo Moon landing, Worden and his two crewmates were dropped in favour of a new back-up crew led by John Young.

Alfred Merrill Worden was born in Jackson, Michigan on 7 February 1932, the first son of Merrill and Helen Worden. He had an older sister, Sally, and a younger, Carolyn. Brothers Jim, Jerry and Peter arrived later.

Their ancestry was from Netherlands farmers, and young Alfred spent much of his time working long hours on the family farm, as he recounted in his highly regarded autobiography, “Falling to Earth” (2011). Farm work allowed him to get his driving licence on his fourteenth birthday, and his first car shortly afterwards. He ended up solely responsible for the farm, livestock and crops, and between times became an accomplished pianist.

A break from farming to study at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor convinced him his future lay elsewhere, and he went on to West Point military academy. That led to the Air Force, then a post as instructor of test pilots.

In 1955 he married Pamela Vander Beek and they had two daughters, Merrill and Alison, but by 1969 the marriage was coming to an end. Divorce had long been taboo for the shiny but unrealistic astronaut image portrayed by the media. Worden’s bosses, now more broad-minded, accepted his decision and allowed him to continue his Moon flight training. He moved across the street from his ex-wife and daughters and remained a part of their life. The protective astronaut wives club, which at first shunned him, relented. He became the first US astronaut whose career survived a divorce.

Worden’s second marriage to Sandra Lee Wilder, a former bullfighter who fought under the name Dixie Lee, did not endure. He married again in 1982 to Jill Lee Hotchkiss, a widow, and adopted her daughter Tamara. That same year Worden ran unsuccessfully in the Republican Primary for Congress in Florida.

Retiring from NASA in 1975, Worden worked on the boards of various aerospace companies, undertook consultancy and travelled widely to lecture. He made appearances on the popular children’s TV show Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, which fuelled the fascination of many children with engineering, science and social issues. Later he was an adviser on First Man, the movie bio-pic of Neil Armstrong. Until 2011 he chaired the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation, which provides scholarships to science and engineering students.

Al was man of great personality and energy who enjoyed lecturing and meeting Apollo enthusiasts of all ages. He would chat readily over a vodka on ice and a smoke, a habit he never gave up, even to train for the Moon! But he also had more athletic recreational interests including bowling, water skiing, golf and racquet ball. Al was known for his relaxed and casual style, sporting a wide assortment of gaily coloured, short-sleeved Hawaiian shirts.

Worden died at a rehabilitation centre in the city of Sugar Land, near Houston, Texas, after a fall. He leaves his three daughters and five grandchildren, plus two sisters and two brothers. His wives pre-deceased him.

With his passing, less than half of the 24 humans who travelled to the Moon in the 1960s and 70s remain alive. A family tribute left on his website (alworden.com) fittingly states: “He was an engaging storyteller who touched the souls of many. We have lost another voice from that great Apollo generation.”

As Al himself would often say upon parting: “Cheers!”